Battle-Tested and Leading Through Uncertainty: COVID-19 and Data Deterioration

By: Lisa Greenwald

04/22/2025

As I mentioned to you in my last blog, when I first took over Greenwald as CEO nearly five years ago, a mentor and colleague called me and my business partner Lisa Weber-Raley, our chief research officer, “battle-tested.” Reflecting on my twenty years with Greenwald and my first years as CEO, “battle-tested” takes on a positive connotation of strength and resilience. (If you haven’t seen Lisa and I in action, alone or together, we’re some smart, tough cookies).

The Uncertainty of COVID-19

One of our most significant tests of leadership came to us immediately, in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. I took the company’s reins in September 2020, which was a very stressful time for our company and our clients. We were not immune to the challenges of that time, and it was a test not only for us as a firm, but also for our clients navigating the same challenges we were confronted with. Living and working through the uncertainty of the pandemic, our initial objective was to ensure the continuity of operations, a feat made possible by our dedicated tech team’s meticulous contingency planning and technological advancements. As we watched many small businesses falter, we persevered.

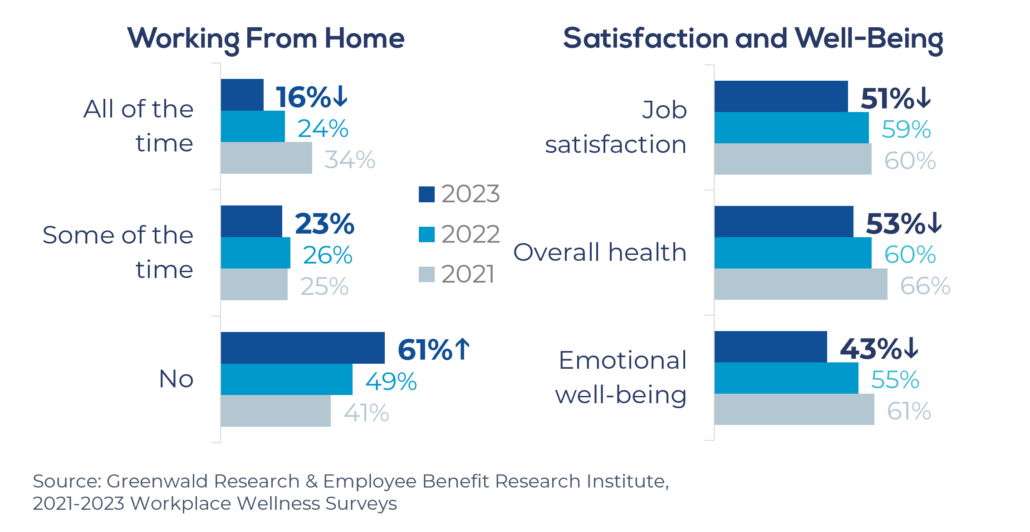

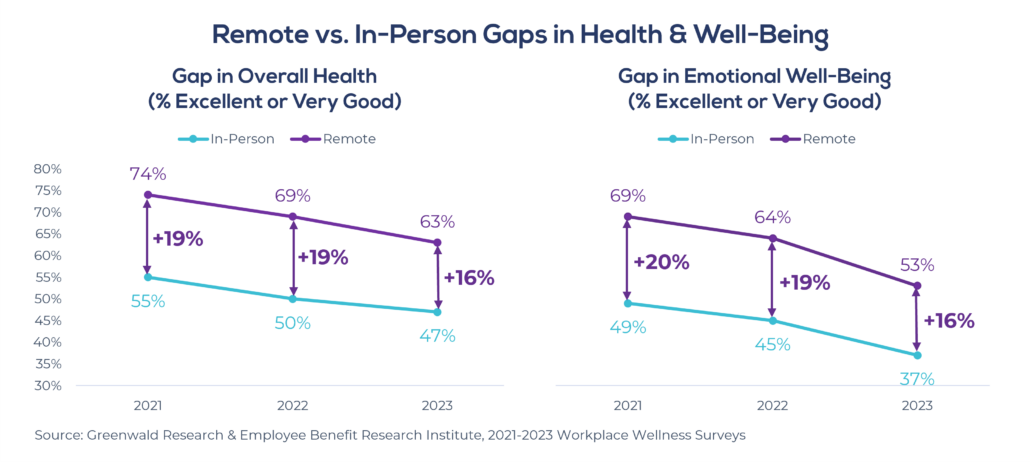

However, the real challenge lay in preserving our organizational culture and fostering camaraderie in a virtual work environment. While the lockdown initially brought my team together in solidarity, the shift to remote work posed unique challenges in maintaining engagement and preventing the onset of meeting fatigue and lower productivity. As an entire team, we continue to work to find the right balance. I know this is an issue that many business leaders face, as companies are beginning to sort through a remote, hybrid, or in-office work environment (If you figure out the answer, I’m all ears).

Navigating Data Deterioration

In the same timeframe, we also managed through the decline of panel and sample data quality. In the research world, observing the deterioration of data quality and its impact on the morale of my dedicated and curious team has been challenging. My team wants to deliver the best for their clients, and outside forces were making us question our results and even the future of our profession. Balancing the pursuit of good results for our clients with the evolving landscape of data quality is an ongoing challenge that requires adaptability and strategic thinking. My team persevered again. We found new partners, using best-in-class quality procedures, developed our own playbooks to combat poor quality, and even built our panel of financial and insurance professionals where we could control the quality of engagement. Once again, we met a challenge and came through the other side of it with solutions and ultimately a better strategy and work product to meet our clients’ needs and enhance the overall experience our clients, both existing and new, will have when they engage with Greenwald.

Staying True to the Vision

The same mentor who described Lisa and me as “battle-tested” was the one who taught us to write a vision and engage in ongoing strategic planning. Visions are cheesy, right? That’s what I thought. Now, I think, for leaders, they are a note to our future selves about what we’re doing and why. It’s our guiding light, most notably when we think we’ve lost our way or times are hard. Staying true to our strategic vision, even during trying times, is essential. That sense of directional purpose and wisdom helped us navigate some challenging times early on in our leadership journey. I advise everyone to make the time to create the vision and plan to help you stay the course and reach your goals.

As I celebrate two decades with Greenwald and the firm celebrates its 40th anniversary, I am grateful for the experiences that have shaped me. As a relatively “new-ish” CEO, I have learned so much from the challenges we have faced. I am so fortunate to work with a team of accomplished research professionals. And I get to lead us forward to the future, along with my tremendous partner, Lisa Weber-Raley, to move us through new challenges and build opportunities. We always come back to the vision, which evolves strategically as well. We are a part of and partners to the health and wealth sectors. We connect people to the answers they need to achieve their vision. We will continue to share what we know, and learn what we don’t to help others succeed and reach their goals.